ADVERTISEMENTS:

The process of the development of thinking has been studied by psychologists and a number of theories have been advanced. The theories are: 1. Piaget’s Theory 2. Sullivan’s Concept of Modes of Thinking 3. Bruner’s Theory 4. Psychoanalytic Theory of Thinking.

1. Piaget’s Theory:

The Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget, using his own children as subjects, devised ingenious and simple experiments and showed how cognitive thought development takes place. He explained behaviour in terms of the individual’s actions and reactions in adapting to his environment.

Unlike animals and birds, human beings have very few instinctive responses and have to constantly evolve new ways and means to deal with the environment. A lamb or chick, few hours after birth, knows how to run away from danger or differentiate between things which are edible and non-edible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In contrast, the new-born human infant often does not know what to eat and what not to eat, let alone being able to recognise danger and is not even capable of recognising the mother. But three or four years later, the lamb or the chick grows up to be a goat or hen and reaches a stage where it can produce milk or eggs.

The child, though not fully capable of taking care of itself, nevertheless reaches a stage where he can run, talk, learn to read and so on. When faced with a danger like a bully in the playground or a stray dog barking and coming towards it, the child may choose to react in any way – run away (like a lamb), hide behind another human being, scream and cry rooted to the same spot or attack by throwing mud or stones.

This ability to think of alternatives distinguishes man from many other animals. The lamb is born with many strong practical instincts while the infant with few. But in the course of development, the human child learns a variety of strategies for solving problems that give a far greater flexibility than the lamb. This is man’s unique capacity for adaptation.

Piaget first became interested in human adaptation when he watched his own children playing. He noticed that the way they approached environmental problems changed dramatically at different ages. He wondered whether it was their coordination which improved or whether older children think differently from their younger brothers and sisters.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Piaget became a keen child-watcher; he played with them, asked questions about their activities, observed them silently for hours together when they were playing alone and with others. He also devised games that would show how they were thinking. Gradually, he understood that there is a pattern.

He realised that all children go through a series of stages as they grew. The stages identified and described by Piaget are the sensory-motor stage, the preoperational stage, the concrete operations stage, and the stage of formal operations.

a. The Sensory-Motor Stage:

The new-born infant sucks anything which is put into his mouth, grasps anything put into his hands, and gazes at whatever crosses his line of vision. You may have seen small children putting everything into their mouth, their own hands, fingers toes, toys and other objects which are within their grasp.

They do not realise that only some objects can be sucked and others not. Similarly, a baby may grasp a rattle, shake it, put it into the mouth, drop it and so on. However, the infant at some point realizes that the noise he has been hearing comes from the rattle. He begins to shake everything he gets hold of trying to reproduce the rattling sound.

Gradually he begins to realise that some things make a noise and others do not. In this way, the infant begins to organise his experiences by fitting them into categories. Piaget calls these categories schemata. They may be considered as simple frameworks which provide a basis for intentional and adaptive problem-solving behaviour in later life.

The child also learns that the objects in the real world, including people, have an existence of their own, independent of its perception of them. This awareness is not present in early infancy. Piaget describes the following experiment with his eight-month old daughter Jacqueline.

“Jacqueline takes possession of my watch which I offer her while holding the chain in my hand. She examines the watch with great interest, feels it, turns it once, says “apff, etc… If before her eyes, I hide the watch behind my hand, behind the quilt, etc. she does not react and forgets everything immediately.”

However, after a few months, i.e. at the end of the sensory-motor period, Jacqueline became quite capable of finding the watch if it was hidden behind the quilt or hand. This shows that she learnt that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen. We often come across a toddler playing with a ball or watching insects when they move under a chair or a cot.

The child begins to search and look for them, because he or she realizes that the ball or insect exists though concealed. This indicates that the child has developed a sense of object permanence or object constancy. This awareness is crucial to cognitive development, for it enables the child to begin to see some regularity in the way things happen.

The perception of regularities is absolutely essential because if every time he encounters a ball or an ant he experiences it as a new stimulus he will never be able to learn to associate the ball or an ant as an external object and that his actions affect them.

Thus, by the end of the sensory-motor stage, the child acquires a kind of ‘motor intelligence’ through direct interaction with his environment. The child knows that his or her actions will have an effect on things outside him or her.

b. Pre-Operational Stage:

The second stage in thought development runs from about two to seven years of age. The child in this stage is action-oriented. His understanding and thought processes are based on physical and perceptual experiences. The child begins to use symbols or representations of events, and form images about everything he encounters.

The most obvious example of representation is the use of words or language and it is at this stage that the child begins to use words to stand for objects. For example, the child is able to talk about things that are not physically present, about lions, tigers, ghosts, etc., though he has not seen them.

Children play a variety of imaginary games where a chair becomes a train or bus, dolls become babies, leaves and flowers become food and so on. They are not fully capable of making a distinction between themselves and the outside world.

They assume that objects have feelings. When playing with dolls, they think that dolls cry, smile and behave like real babies. They consider their own psychological processes, such as dreams, to be real and concrete events.

Piaget found that children at this stage tend to focus their attention on a single aspect of an object or an event that attracts their attention, ignoring all other aspects. This was demonstrated in the following famous experiment. Children were asked to fill two identical” containers with beads.

When they had finished, Piaget poured the beads from one container into a tall thin glass and asked them if one had more beads than the other. Invariably, the children said ‘yes’, even though they realised he had not added or taken away any beads. This illogical response arises because children can only think about one aspect or dimension at a time, i.e. height or width. Piaget calls this single-mindedness.

Piaget found that thinking during this stage is rigid and ‘irreversible’. J.L. Phillips gives an interesting example of irreversibility. He asked a four-year old boy if he had a brother; the child replied ‘yes’. He then asked the brother’s name; the answer was ‘Jim’. ‘Does Jim have a brother?’ The child responded with a definite ‘no’.

This illustrates that the child could not reverse the principle underlying the same concept, i.e. of having a brother. Another feature identified in the above illustration is the child’s inability to think of himself as somebody else’s brother. This inability to put himself in Jim’s position and see himself as a brother is an example of egocentricism.

Another interesting aspect of pre-operational thinking identified by Piaget is the concept of conservation. In the pre-operational period, the child does not know how to ‘intellectually conserve’.

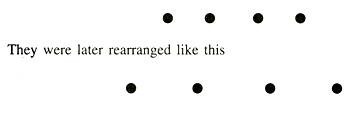

In his experiment, four marbles were arranged in the following pattern in front of the child:

The child steadfastly maintained that the rearrangement contained more marbles. Piaget explained that at this point the child is struck by the visual-spatial evidence at that moment rather than by the knowledge that these are the same four marbles in new positions.

The child cannot realise and maintain the fact that the same number of marbles could occupy more space. Piaget terms this, as an inability to ‘conserve’ the idea of number. The child also has difficulty conserving other qualities of stimuli such as volume, mass, etc.

The concept of conservation of volume was demonstrated in a simple experiment using containers of different shapes and water. Transparent glass containers A, B, C and D, as shown in Fig. 11.2, were placed in front of a child. The containers B and C had identical quantity of water. The experimenter poured water from the container B into A.

When the child was asked whether the amount of water contained in A is the same as in C, the child unhesitatingly pointed towards container A (the taller one) and said that it contains more water. Similarly, when the water from C was poured into D and the child was asked whether the quantity of water in A and D is equal, the answer was that the quantity of water in A is more.

The above experiment demonstrates what Piaget would call an inability to conserve. The child’s idea or estimation of the quantity of water was influenced by the size, height, shape and other characteristics of the containers. The child’s estimation of the quantity of water showed a lack of stability and definiteness and appeared to depend on the characteristics of the containers.

c. Concrete Operations Stage:

During this stage, which usually occurs between 7 and 11 years, the child acquires basic notions of time, space, number, etc. and also a flexibility which was lacking in the pre-operational stage. The child, during this stage, learns to retrace his thoughts, correct himself, start working right from the beginning if necessary, consider more than one dimension at a time and to look at a single object or problem in different ways. Three logical operations characterize thinking at this stage: combining, reversing and forming associations. These operations can be illustrated with a simple example.

Ask children of different ages, say below seven years and above seven years “Supposing, you are given this coin (showing a one rupee coin) to buy chocolates. If the shop owner gives you two chocolates in exchange for this coin (one rupee coin), how many chocolates would you get in exchange for these four coins (showing four coins of twenty five paise)”. Children under seven may come out with responses like four chocolates or eight chocolates and so on.

However, children above seven, in the concrete operations stage, will be able to distinguish and combine all the small coins (twenty five) into a superclass of hundred paise or one rupee. They will also be able to conserve this process of adding four twenty five-paise coins into a single coin or reduce single one rupee coins to four twenty five-paise coins.

They are also capable of associating a twenty five-paise coin with other coins like two ten-paise coins and one five-paisa coin. Children at this stage, although quite logical in their approach to problems, can only think in terms of concrete things they can handle or imagine handling. But an adult is capable of thinking in abstract terms to formulate tentative suggestions or hypotheses and accept or reject them without testing them empirically. This ability is said to develop in the next stage.

d. Formal Operations Stage:

A remarkable ability is acquired in this fourth and final stage, which occurs between 11 and 15 years of age. To demonstrate the development of abstract thinking Piaget conducted a simple experiment. He gave an opportunity to the children to discover for themselves Archimedes principle of floating bodies.

Children in the concrete and formal operations stage were given a variety of objects and were asked to separate them into two groups: things that would float and things that would not. The objects included cubes of different weights, matches, sheets of paper, a lid, pebbles and so on. Piaget then let the children test their selections in a tub of water and asked them to explain why some things floated and others sank.

The younger children were not very good at classifying the objects and when questioned, gave different reasons. The nail sank because it was too heavy; the needle because it was made of iron; the lid floated because it had edges and so on. The older children seemed to know what would float.

When asked to explain their choices they began to make comparisons and cross-comparisons, gradually coming to the conclusion that neither weight nor size alone determined whether an object would float; rather it was the relationship between these two dimensions. Thus, they were able to approximate Archimedes principle (objects float if their density is less than that of replaced water). The fact that these children searched for a rule or a principle is what makes this stage of development superior and significant.

Younger children find reasons by testing their ideas in the real world. They are concrete and specific. While children at the formal operations stage and beyond go further than testing the, ‘here and now’; they try to consider possibilities as well as realities and develop concepts.

Thus, we see that at the final stage, the individual is able to arrive at generalisations, and real thought processes begin to develop. Piaget’s developmental theory essentially concentrates on the structural and formal characteristics of thinking. He believes that his scheme of the development of thinking is universal. Piaget introduces a number of concepts like adaptation, accommodation, assimilation, centering, decentering, etc. It is not necessary to go into these concepts here.

2. Sullivan’s Concept of Modes of Thinking:

Yet, another approach to the development of thinking comes from the views of H.S. Sullivan who was a leading psychoanalyst. Sullivan postulates three basic modes. The first and the earliest one is called the prototaxic mode. This stage operates in the first year of an individual’s life and during this stage one has no awareness of oneself or one’s ego. Thought process is mostly in the form of a feeling or apprehension. Thought, therefore, does not have a definite structure and is vague.

The next is the parataxic mode. During this stage the global or undifferentiated response gives way to specific elementary thought images and contents. Logical operations do not occur yet. According to Sullivan the autistic state of communication reflects a parataxic mode. Thought process is still confused and vague and almost comparable to the prelogical stage described by Piaget.

The final stage which is known as the syntaxic mode represents the development of logical thought processes, enabling the integration and organisation of symbols. It is at this stage that thought becomes clear with the possibility of logical operations. This stage would correspond to the stage of formal operations described by Piaget.

A distinction, however, may be made in that, while Piaget’s theory was specifically a theory of thinking, Sullivan does not deal with thinking exclusively. His concept of modes is more or less a view of cognitive organisation in general, a process by which the individual perceives and experiences the environment, which necessarily includes thinking.

3. Bruner’s Theory:

Yet, another approach to the development of thinking was outlined by Jerome S. Bruner, who like Piaget, observed the process of cognitive development or development of thinking. Bruner also postulated certain stages. The stages formulated by him are enactive, iconic, and symbolic representations which are considered more or less comparable to Piaget’s preoperational, concrete operational and formal operational stages. However, Bruner differed from Piaget in focusing on the representations the child uses in thinking rather than on the operations or manipulations which take place in the process.

Bruner uses Piaget’s experiments to explain his point of view of cognitive development which is briefly described below:

a. Enactive Representation Stage:

A child at this stage adopts the most basic or primitive ways of converting immediate experience into a mental model. This mode of conversion is usually non-verbal and is based on action or movement. Thus, a child’s representations of objects and events in terms of appropriate motor responses or ‘acting out’ are known as enactive representation. Bruner cites Piaget’s experiment to explain this stage.

“A baby drops a rattle through the bars of its crib. It stops for a moment, brings its hand up to its face, and looks at its hand. Puzzled, it lets its arms fall and shakes the hands as if the rattle were still there; no sound. It investigates its hand again.”

Bruner suggests that in this situation, the child is representing the rattle when it shakes its hand, that is the rattle means shaking its hand-and hearing a noise. Gestures are enactive representations. For instance thumbs up means victory; index finger on your lips means silence, and so on.

b. Iconic Representation:

An icon or an image or a pictorial representation is considered to be the method of converting immediate experience into cognitive models using sensory images. This stage was explained by extending Piaget’s study which was described in the previous stage. The child a few months later when it drops the rattle tries to look over the edge of its crib.

When an adult picks it up or if the child is unable to see it, the child may- start screaming and crying. According to Bruner, this sense of loss indicates that the child has an image of the rattle in its mind and that it now distinguishes between shaking his hand and the rattle. This type of ‘picturing’ things to oneself is called iconic representations thinking.

c. Symbolic Representation:

As the child grows, it reaches a stage where its cognitions are not always dependent on motor activities or images and pictures. Its cognitive process begins to function in terms of symbols. The symbols do not depend on images or concrete appearances. For example, the word ‘giri’ neither looks nor sounds like a female child.

Similarly, the number eight does not resemble the quantity eight. Consider a simple arithmetic problem. A boy has four mangoes and he buys two more. How many does he have? A child of five or six years may solve the problem by drawing four and two mangoes and counting them, while an older child may write the numbers, four and two, and adds them up without imagining the mangoes.

4. Psychoanalytic Theory of Thinking:

It would have been surprising if an all-embracing theory like Freudian psychoanalysis did not make its contribution, though indirectly, to our understanding of the process of thinking. The Freudian theory of development with its concept of different stages like oral, anal, phallic and genital, drew several conclusions for the understanding of thinking.

According to Freud, the early period of infancy is characterised by what is called narcissistic thinking, wherein the thought process contains a high tint of wish fulfillment. Freud refers to certain terms like omnipotence of the wish and the omnipotence of thought or word.

The stage of omnipotence of the wish is characterised by the fact that this stage thought is highly coloured by instinctual impulses, a total absence of distinction between reality and non-reality. The next stage shows what he calls omnipotence of thought. Here thinking becomes symbolic and verbalized but still remains highly egocentric.

It is only at a later stage that thinking becomes objective and a distinction emerges between the inner self and the outer world. Thought comes more and more under the influence of perception and is emancipated from the stranglehold of instinctual impulses. During the latency period, the thinking process expands and according to Anna Freud, there is an enrichment of fantasy and abstract thinking.

Thought, according to Freud, is an integral part of the total function of living and the nature of the thought process reflects the overall developmental stage of life itself. In simple terms, thinking is one of the mechanisms of living and plays a vital role in the overall process of- adjustment. Freud says that there is a thin dividing line between reality and fantasy. If this is true, then, thinking is to fantasy what living is to reality.

Theories of Thinking – Points of Consensus:

In the above paragraphs an attempt has been made, perhaps in slightly extravagant detail, to present different explanations of the nature and development of thinking. No doubt these different approaches differ among themselves but certain points of consensus seem to emerge.

These may be summarised as follows:

(a) Basically all theories agree that in the earlier stages thought is essentially sensory-motor in character and is bound by immediate sensory experiences.

(b) At the second level a distinction emerges between sensory experience and thought, due to the development of the capacity to form images and later, thought gets separated from sensory experience.

(c) At the third level the capacity to use symbols, words and ideas emerges along with the expanded capacity for forming imagery. Thought is both concrete and abstract and is still influenced by inner processes – it is egocentric.

(d) At the final level thought becomes an independent process, relatively free of concrete experience, capable of interpreting and organising the same and goes beyond the ‘here and now’.

(e) Abstract thinking emerges.

It may be seen that most of the theorists agree on these general features. Individuals differ with regard to the rate at which this process of development occurs and also the extent to which they go through to the last of these stages. Some individuals tend to remain at the egocentric or concrete levels while others go beyond.

It is also possible that some individuals, after reaching a certain stage, can be thrown back to an earlier level of thinking when confronted with severe psychological crisis. Thus there can be a process of regression in thinking. Autistic children provide evidence where thinking has not proceeded beyond the most elementary level, whereas psychotic patients provide clear evidence of a regressive process.

It may further be pointed out that the process of development of thinking is very much influenced by all the factors which influence development in general. The process of socialization, education, personal experiences, etc., all influence the development of thinking. In brief, the process of thinking develops along with the person.