ADVERTISEMENTS:

List of top six psychological experiments on socialization!

Experiment # 1. Formation of Spontaneous Groups:

Introduction:

One of the properties of a larger group is that it always includes within it a number of smaller, spontaneous or informal groups, e.g., in a class which is a large group there can be several subgroups consisting of a small number of students. These small groups are formed on the basis of spontaneous attraction.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This attraction itself can be due to several factors like resemblance in sex, size, likes and dislikes, etc. Sometimes a small spontaneous group may form around a particular member who has some distinctive qualities even though he may not reciprocate the same amount of liking for the others. Such a person may sometimes attract a large number of followers or admirers.

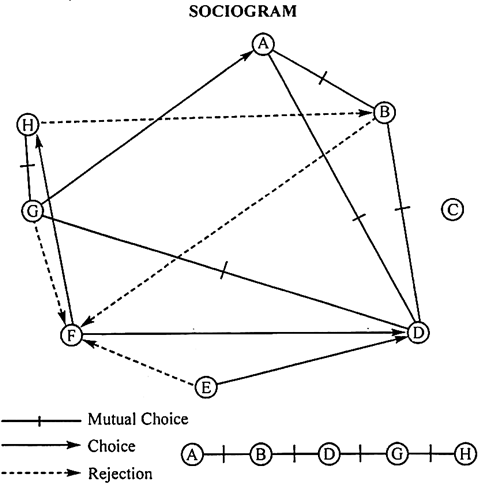

He is known as a ‘star’. There may be some individuals on the other hand who may not attract any other member. These individuals are called ‘ isolates’. Some members may be actively ‘ rejected’. Sometimes three or four members may form a close knit sub-group brought together by strong and mutual attraction. Such a group is called a ‘clique’.

To study these phenomena, Moreno devised a very simple technique called ‘sociometry’. The method consists of requesting the members of the group to express their preferences or choice of companions to undertake certain activity. The questions can be put in either a positive or a negative form.

An example of positive question- ‘I want you to take the help of two other students from your class and organise a small function today; whom would you like to choose?’ Mention the names of the two. An example of negative question ‘I want to split this class into small groups of three to do different things for the school’s annual day. Of course, I don’t want you to work with those whom you don’t like. Tell me the names of the people whom you would like to avoid.’

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Problem:

To study the nature of spontaneous group formation in the given group.

Materials Required:

Two sociometric questions, one positive and the other negative.

Procedure:

The students are asked to write down their answers to these questions on a piece of paper, and hand it over in confidence to the teacher.

Results:

1. Calculate the total frequency of likes secured by each individual and find out whether there is a large variability, the number of ‘stars’, if any, the number of ‘isolates,’ if any.

2. Plot the results in the form of a sociogram and analyse how many closed cliques are there. Try to analyse the reason for clique formation by comparing the various physical and personal qualities of the members.

3. Try to analyse the qualities of the stars and the isolates.

4. Analyse the scores of rejection for the various members.

5. Study the physical and personal qualities of the strongly rejected members.

6. How many of the isolates are also strongly rejected?

Practical Application:

This technique has important application in selecting students to form informal study groups, to select teams from among a large group of workers in an industry, and also in locating leaders in different groups.

As per the above diagram, individual ‘A’ is ‘Star of the group, C is an isolate and F is a reject.

Experiment # 2. Social Facilitation:

Introduction:

An important question which was attempted an answer by social psychologists experimentally relates to the differences in an individual’s work output when he works alone and when he works in a group situation. In his very early experiments, F.H. Allport found that individuals turned out much more work while working in a group situation, in simple tasks. He called this phenomenon ‘Social Facilitation’. Subsequently, several experiments have been done on this problem.

Problem:

To demonstrate the phenomenon of social facilitation.

Materials Required:

A vowel cancellation test, a list of simple mathematical problems, a stopwatch.

Procedure:

The experiment is done under two conditions:

(1) Individual condition, and

(2) Group situation.

(1) Individual Condition:

Handover the vowel-cancellation test to each subject seated alone and ask him to cancel out all the A’s and E’s until he is asked to stop. After ten minutes count the number of As and Es cancelled.

Similarly handover the sheet of mathematical problems and ask her/him to go on solving as many problems as possible until he is instructed to stop. Allow ten minutes.

Count the number of problems correctly solved.

(2) Group Situation:

Seat all the members of the group together and repeat the experiment with both vowel cancellation and the mathematical problems. Allow ten minutes for each.

Results:

Tabulate the results for the group as follows:

1. Compare the performance under the two conditions.

2. In the case of the problems find out whether there is an increase in both the number attempted and the number of correct solutions under the group situation.

Note:

Try the experiment using the following procedure:

A. Instead of putting the subject in an actual group situation, seat him alone and tell him that other members of his group are doing the same work in another room. Study the nature of facilitation now.

B. The role of competition. Introduce a competitive motivation by announcing reward for the best performance. Repeat the experiment under competitive conditions, both in individual and group conditions.

Experiment # 3. Effect of Group Opinion on the Individual’s Judgement:

Introduction:

The basic premise of social psychology is that the individual is influenced by the values, standards and attitudes of the groups to which he belongs. Studies on socialisation have been dealing with this process of how the group influences the basic personality pattern of the individual. Laboratory experiments have attempted to study the influence of contemporaneous group pressure on momentary and simple judgements of the individuals.

The early experiments of Asch proved the influence of group pressure in judging lengths of lines. Sheriff’s experiments on autokinesis are less relevant here. Crutchfield in a very interesting experiment showed how group pressures influence individual subject’s opinion on different issues.

Problem:

To demonstrate the influence of group opinion on an individual’s perceptual judgements.

Procedure:

A good number of marbles are kept in a plate and covered with a cloth. The cover is removed and each subject is shown the plate for a period of 20 to 30 seconds. After this he is instructed to guess the number in the plate. The subject writes down the figure on a piece of paper and secretly hands over to the experimenter.

As soon as all the subjects have made their guesses, the experimenter simply writes down the guessed figures on the notice board, so that all the subjects can see them. These are shown to the subjects for about 5 to 10 minutes.

After this the subjects are again individually shown the marbles as before and required to make a guess.

Results:

The results are tabulated as follows:

1. Find out whether many subjects guess differently the second time.

2. If so, in what direction? See if it is in the direction of the group average.

Experiment # 4. The Influence of Individual Instruction and Group Discussion on Attitudes:

Introduction:

One of the important aims of education is to change the attitudes of individuals. Solutions to many social problems necessarily involve bringing about desirable changes in the attitudes of individuals towards certain issues such as changing traditional and outmoded customs and attitudes, resolving intergroup conflicts etc.

In such instances two methods have been tried:

1. Instructing and educating the individual subjects.

2. The group discussion method which has been found to be quite useful.

Problem:

To study the comparative effectiveness of individual instruction and group discussion in changing certain attitudes.

Materials Required:

A scale of conservatism-radicalism.

Procedure:

The experiment is done as a group experiment. The scale of conservatism-radicalism is administered to the entire class and on the basis of the scores the class is divided into three groups with more or less equal average scores. (Matched groups). Out of this, the first group ‘A’ is the control group; the second group, ‘B’ is the experimental group which is subjected to individual instructions and the third group ‘C’ another experimental group which is subjected to the group discussion method.

After the groups are separated the experimenter takes each member of group ‘B’ separately and explains to him the nature of the changing society and the need for people to give up many of the old ideas and customs. The individual instruction should be made as convincing as possible. With group ‘C’ a different procedure is followed.

The experimenter sits along with all the members in the group and discusses in an informal manner- the various issues covered by the conservation radicalism scale. This is done in an indirect manner and the discussions are directed in a subtle way towards convincing the group of the necessity to give up many of its conservative ideas. Care must be taken to elicit participation in the discussion by as many of the members of the group as possible. The attitude scale is administered to all the members again.

Results:

The results are tabulated as follows:

Find out whether the scores have changed in all the groups. If so which group exhibits the maximum change? The change shown by group ‘B’ minus the change shown by group ‘A’ indicates the influence of individual instruction. The change in group ‘C’ minus the change in group ‘A’ indicates the influence of group discussion.

Compare the extent of influence of the two methods and test the significance of difference.

Experiment # 5. Competition, Co-Operation and Work Output:

Introduction:

Social psychologists have undertaken several experiments in are of group dynamics to compare the efficiency of different types of groups in performing different tasks. Some of the important dimensions of group variation studied are autocratic vs. democratic groups; cooperative vs., competitive groups, etc. The experiment described below is a model of several experiments carried out on co- operative and competitive groups.

Problem:

To make a comparative study of cooperative and competitive groups with reference to task output.

Materials Required:

A large number of simple tasks of more or less equal difficulty- examples of such tasks are solving problems, fitting the parts of familiar objects, deciphering codes, etc.

Procedure:

The experiment is done as a group experiment Care should be taken to see that the subjects do not have prior knowledge of the experiment. The group is divided into two, after matching the subjects with reference to age, intelligence, previous experience on tasks similar to the ones in the present experiment, etc. One of these groups is called the co-operative group and the other the competitive group. A number of sets of tasks to be employed are kept in two piles identical with each other.

a. Co-Operative Group:

This group is instructed as follows- “This is a test to find out how different individuals perform certain tasks together. All of you belong to one single group. There are several small groups similar to this one, which are also working in different rooms. Out of these groups the group whose performance is the best will be selected for an inter- school contest. All of you have to work together and what matters is the performance of the group as a whole. All the members of the winning group will be given similar prizes.”

The group is then allowed to work on the different tasks for a fixed time, say 30 minutes. The experimenter keeps note of the number of tasks attempted by the various members and also notes the errors and correct solution.

b. Competitive Group:

The competitive group is instructed as follows:

“Like your group several other groups are also working on certain tasks. This is part of a contest between groups. The group which does best will receive a prize. In addition, the individual member who solves the highest number of tasks will also be given a prize.” This group is also allowed to work on the task for a period of 30 minutes.

Results:

Tabulate the results as follows:

1. Compare the two groups with reference to the number of tasks attempted and the number of correct solutions.

2. Test the significance of difference, in the performance of the cooperative group and the competitive group.

3. Take the introspective reports of the individual members of the two groups and compare the reactions of the members of the respective group to their experience.

Experiment # 6. Cognitive Dissonance:

Introduction:

Cognitions can be described informally as any knowledge, opinion or belief about the environment, one’s behaviour and one’s self. Leon Festinger who developed the theory of cognitive dissonance refers to cognitive elements as attitudes. The term dissonance is introduced to represent inconsistency or incompatibility between two or more cognitive elements.

Consistency between two cognitive elements represents consonance. Attitudes of an individual are normally consistent with each other. Hence his actions are in accordance with his attitudes, leading to a pleasant state of mind.

We shall consider dissonance, because it is an aversive state which arises when the individual is aware of an inconsistency or conflict within himself and he is motivated to reduce or dispel this condition in some way. For example, if a person knows that the most he could afford to pay for a new automobile was Rs. 20,000 and he had just been persuaded to sign a contract to purchase, one costing Rs. 25,000, there would be a dissonant relation between two cognitive elements.

The theory of cognitive dissonance was applied to a variety of situations in the social context to study attitudes and attitudinal change.

Festinger and Carl Smith tested the following hypotheses, which formed the core of the theory:

1. If a person is induced to say or do something contrary to what he believes he will tend to modify his attitude so as to make it consonant with the cognitions of what he has said or done.

2. The greater the pressure used to elicit behaviour which is contrary to one’s private attitude- the less his attitude will change.

However, whether dissonance occurs or not depends upon the individual’s personal experience and outlook. There is no dissonance if he does not perceive an inconsistency in his attitudes and behaviour. Dissonance can be reduced not only through attitudinal change but also thorough rationalizing, perceiving selectively and by seeking new information.

Problem:

To study the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance.

Materials:

Six packets of cigarettes of different brands.

Procedure:

The experiment is carried out as a group experiment. A group of nine boys who are smokers are selected as subjects. They are divided into three groups A, B & C, three in each group. The subjects are requested to rate each brand of cigarettes on a 11 point scale of desirability. The experimenter makes sure that every member of the group rates brands.

Each subject of Group ‘A’ is given a packet containing that particular brand of cigarette which he rated as very high. Each subject of Group ‘B’ is given a packet of that particular brand which he rated as third highest, i.e., the brand which he rated as slightly less desirable. Each subject of group ‘C’ is given two packets of that particular brand which is rated as having very low desirability.

The experimenter calls for a break of 10 minutes and requests the subjects to remain in the hall. He permits them to have a cigarette from their packet if they feel like. Later, all the subjects are asked to rate all the brands for the second time. Each brand of cigarette is rated on a 11 – point scale of desirability.

Precaution:

The experimenter should make sure that different brands are of the same size and of approximately the same price.

Results:

The results are tabulated as follows:

Comparison of the three groups:

Compute t-ratio for testing the significance of difference between the means (mean of the differences between the first and the second ratings) of Group A and B; A and C; B and C.

Discuss the results in light of the hypotheses formulated.