ADVERTISEMENTS:

To study personality scientifically, we must first be able to measure it. How do psychologists deal with this issue? As we’ll soon see, in several different ways.

1. Self-Report Tests of Personality: Questionnaires and Inventories:

One way of measuring personality involves asking individuals to respond to a self-report inventory or questionnaire. Such measures (sometimes known as objective tests of personality) contain questions or statements to which individuals respond in various ways.

For example, a questionnaire might ask respondents to indicate the extent to which each of a set of statements is true or false about themselves, the extent to which they agree or disagree with various sentences, which of a pair of activities they prefer.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By way of illustration, here are a few items that are similar to those appearing on one widely used measure of the “big five” dimensions of personality. Persons taking the test simply indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each item (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree).

I am very careful and methodical.

I generally get along well with others.

I cry easily.

Sometimes I feel totally worthless.

I have a lot of trust in other people.

Answers to the questions on these objective tests are scored by means of special keys. The score obtained by a specific person is then compared with those obtained by hundreds or even thousands of other people who have taken the test previously. In this way, an individual’s relative standing on the trait being measured can be determined.

For some objective tests, the items included have what is known as face validity. Reading them, it is easy to see that they are related to the trait or traits being measured. For instance, the first item above seems to be related to the conscientiousness dimension of personality; the second is clearly related to the agreeableness dimension. On other tests, however, the items do not necessarily appear to be related to the traits or characteristics. Rather, a procedure known as empirical keying is used.

The items are given to hundreds of persons belonging to groups known to differ from one another for instance, psychiatric patients with specific forms of mental illness and normal persons.

Then the answers given by the two groups are compared. Items answered differently by the groups are included on the test, regardless of whether these items seem to be related to the traits being measured. The reasoning is as follows- As long as a test item differentiates between the groups in question groups we know to be different then the specific content of the item itself is unimportant.

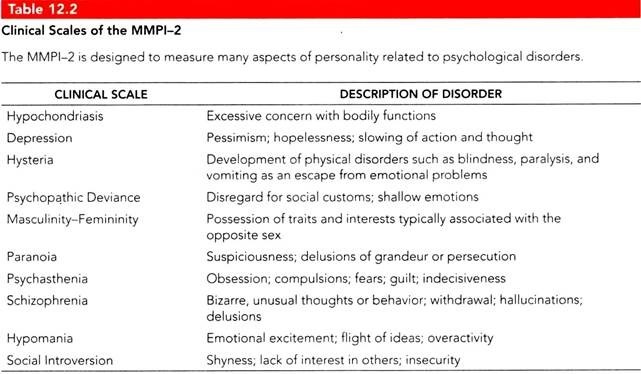

One widely used test designed to measure various types of psychological disorder, the MMPI, uses precisely this method. The MMPI (short for Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) was developed during the 1930s but underwent a major revision in 1989. The current version, the MMPI-2, contains ten clinical scales and several validity scales. The clinical scales, which are summarized in Table 12.2, relate to various forms of psychological disorder.

Items included in each of these scales are ones that are answered differently by persons who have been diagnosed as having this particular disorder and by persons in a comparison group who do not have the disorder. The validity scales are designed to determine whether and to what extent people are trying to fake their answers for instance, whether they are trying to seem bizarre or, conversely, to give the impression that they are extremely “normal” and well-adjusted. If persons taking the test score high on these validity scales, their responses to the clinical scales must be interpreted with special caution.

In India, an attempt similar to MMPI was made in the form of the Jodhpur Multiphasic Personality Inventory by Joshi and Malik (1983) using original pool of items. The inventory provides scores for four broad categories: psychoneurosis, psychosis, psychosomatic disorders, and validity indices.

The scales are listed below:

i. Psychoneurosis Scales are measures of anxiety, phobia, obsessive compulsive reactions, conversion reactions, hysteria-dissociation, neurotic depression, and neurasthenia. Besides these clinical scales, it also includes a measure of social introversion.

ii. Psychosis scales consist of schizophrenia simple, heberphrenia, schizophrenia-paranoid, paranoia, manic depression, and psychotic depression.

iii. Psychosomatic scales consist of scales for diagnosis of peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, hypertension, bronchial asthma, and anorexia nervosa.

Also there are three validity scales similar to MMPI validity scales namely L, F, and K.

Another widely used objective measure of personality is the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI). Items on this test correspond more closely than those on the MMPI to the categories of psychological disorders currently used by psychologists. This makes the test especially useful to clinical psychologists, who must first identify individuals’ problems before recommending specific forms of therapy for them.

Another objective test, the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI), is used to measure aspects of personality that are not directly linked to psychological disorders. Specifically, it measures the “big five” dimensions of personality. Because these dimensions appear to represent basic aspects of personality, the NEO Personality Inventory has been widely used in research. A frequently used personality test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, was developed to classify people as to their style of thinking, in Jungian terms.

A person may be classified as dominated by sensation, thinking, feeling, or intuition. It is often used for the purpose of vocational guidance. Thus the thinking style might be appropriate for a lawyer, the sensation style might be appropriate for an athlete, and the feeling style for a poet, and intuitive style for the job of a clinical psychologist.

2. Projective Measures of Personality:

In contrast to questionnaires and inventories, projective tests of personality adopt a very different approach. They present individuals with ambiguous stimuli—stimuli that can be interpreted in many different ways.

Persons taking the test are asked to indicate what they see, to make up a story about the stimulus, and so on. Since the stimuli themselves are ambiguous, it is assumed that the answers given by respondents will reflect various aspects of their personality. In others words, different persons will see different things in these stimuli because these persons differ from one another in important ways.

For some projective tests, such as the TAT, which is used to measure achievement motivation and other social motives, the answer appears to be yes, such tests do yield reliable scores and do seem to measure what they are intended to measure. For others, such as the famous Rorschach test, which uses inkblots such as the one, the answer is more doubtful.

Responses to this test are scored in many different ways. For instance, one measure involves responses that mention pairs of objects or a reflection (e.g., the inkblot is interpreted as showing two people, or one person looking into a mirror).

Such responses are taken as a sign of self-focus excessive concern with oneself. Other scoring involves the number of times individuals mention movement, color, or shading in the inkblots. The more responses of this type they make, the more sources of stress they supposedly have in their lives.

Are such interpretations accurate? Psychologists disagree about this point. The Rorschach test, like other projective tests, has a standard scoring manual that tells psychologists precisely how to score various kinds of responses. Presumably, this manual is based on careful research designed to determine just what the test measures.

More recent research, however, suggests that the scoring advice provided by the Rorschach manual may be flawed in several respects and does not rest on the firm scientific foundation psychologists prefer. Thus, projective tests of personality, like objective tests, may vary with respect to validity. Only tests that meet high standards in this respect can provide us with useful information about personality.

3. Other Measures: Behavioral Observations, Interviews, and Biological Measures:

While self-report questionnaires and projective techniques are the most widely used measures of personality, several other techniques exist as well. For instance, the advent of electronic pagers now allows researchers to beep individuals at random (or pre-established) times during the day in order to obtain descriptions of their behavior at these times. This experience sampling method can often reveal much about stable patterns of individual behavior; and these, of course, constitute an important aspect of personality.

Interviews are also used to measure specific aspects of personality. Psychoanalysis, of course, uses one type of interview to probe supposedly underlying aspects of personality. But in modern research special types of interviews, in which individuals are asked questions assumed to be related to specific traits, are often used instead.

For instance, interviews are used to measure the Type A behavior pattern, an important aspect of personality closely related to personal health. As we’ll see shortly, persons high in this pattern are always in a hurry they hate being delayed. Thus, questions asked during the interview focus on this tendency; for instance: “What do you do when you are stuck on the highway behind a slow driver?”

In recent years several biological measures of personality have also been developed. Some of these use positron emission tomography (PET) scans to see if individuals show characteristic patterns of activity in their brains patterns that are related to differences in their overt behavior. Other measures focus on hormone levels for instance, the question of whether highly aggressive persons have different levels of certain sex hormones than other persons. Some results suggest that this may indeed be the case.

4. Personality and Health: The Type A Behavior Pattern, Sensation Seeking, and Longevity:

Back in the 1960s, two cardiologists, Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman (1974) noticed an interesting fact- When a worker came to reupholster the furniture in their office, the fronts of the cushions on the chairs were worn down, as if their patients had sat on the very edge of the seats.

They followed up on this observation, and soon realized that many of the people they treated for heart attacks seemed to show a similar cluster of personality traits: They were always in a hurry, highly competitive, and hostile or easily irritated. Even during medical examinations they looked at their watches repeatedly; and if they had to wait to see the doctor, they tended to express their annoyance openly.

These observations led the physicians, and soon psychologists too, to develop the concept of the Type A behavior pattern a cluster of traits that predispose individuals toward having heart attacks. Indeed, researchers soon noted that Type As (as they are termed) are more than twice as likely to suffer serious heart attacks as Type Bs (persons who are not always in a hurry, irritable, or highly competitive). In short, one cluster of personality traits seemed to be strongly linked to an important aspect of personal health—in fact, to a life-threatening aspect of health.

Why do Type As experience more heart attacks than other persons especially, than Type Bs? For several reasons. Type As seem to seek out high levels of stress: They take or more tasks and more responsibilities than other persons. They experience higher physiological arousal when exposed to stress than other persons, and they are reluctant to take a rest after completing a major task; on the contrary, they view this as a signal to start the next one. These and other tendencies shown by Type As (especially their irritability) seem to ensure that they are always stirred up emotionally; and this, in turn, may increase the chances that they will become the victims of heart attacks.

Interestingly, additional research suggests that it is the cynical hostility of Type As their suspiciousness, resentment, anger, and distrust of others that is most directly linked to their cardiac problems. Whatever specific components are most central, though, it seems clear that this is one aspect of personality with important implications for individuals’ health and well-being.

Fortunately, individuals can learn to reduce their tendency toward Type A behavior; they can learn to be more patient, less competitive, and less irritable or suspicious. Having the characteristics of a Type A is not necessarily a death sentence. Unless individuals take active steps to counter their own tendencies toward the Type A pattern, however, they do appear to be at risk.

Sensation Seeking:

Now, let’s consider another aspect of personality that can strongly influence personal health, sensation seeking, or the desire to seek out novel and intense experiences. Persons high on this characteristic want lots of excitement and stimulation in their lives, and become intensely bored when they don’t get it. This, in turn, leads them to engage in many high-risk behaviors, such as driving fast, experimenting with drugs, climbing mountains, and taking risks where sex is concerned.

An extreme example of such high-risk behavior is provided by people who engage in BASE jumping—they jump off high buildings, bridges, and cliffs with a small parachute. For instance, Thor Axel Kappfjell jumped off the World Trade Center in New York in 1998, floating safely to the bottom of the 110-story building. However, his luck ran out in 1999, when he was killed by smashing into a 3,300-foot cliff in his native Norway.

What accounts for this preference for high levels of stimulation? Marvin Zuckerman (1990, 1995), the psychologist who first called attention to sensation seeking as an aspect of personality, believes that it has important roots in biological processes. High sensation seekers, he suggests, are persons whose nervous systems operate best at high levels of arousal.

Zuckerman (1995) notes that high sensation seekers may have a high optimal level of activity in what is known as the catecholamine system, a system within the brain that plays a role in mood, performance, and social behavior. In a sense, the “thermostat” for activity in this neurotransmitter system is set higher in such persons than in most others, and they feel better when they are receiving the external stimulation that plays a role in activation of this system.

Whatever the precise roots of high sensation seeking, though, it is clear that persons showing this characteristic do often engage in behaviors that expose them to danger. Sensation seeking has survived as a trait, which suggests that the benefits it yields more than offset these potential costs; but the costs are real, nonetheless.

The results of one of psychology’s longest-running studies research first begun in 1921 indicate that people high in conscientiousness, one of the “big five” dimensions of personality, may well live longer than persons lower on this dimension. This study focused on 1,528 bright California boys and girls who were about eleven years old when the research began. (Because the study was started by Lewis Terman, participants referred to themselves as “Termites.”)

The same persons have been tested repeatedly for almost eighty years, thus providing psychologists with an opportunity to learn whether aspects of personality are related to how long people live. When the study began, of course, the big five dimensions had not yet been identified. However, the children were rated on characteristics closely related to this concept, including carefulness, dependability, and orderliness. Results have indicated that participants rated high on such traits were fully 30 percent less likely to die in any given year than persons low in these traits.

Why has this been the case? The study is correlational in nature, so we can’t tell for sure, but part of the answer seems to involve health-related behaviors: Persons high in conscientiousness are found to be less likely to abuse alcohol, to smoke, and to engage in other behaviors that put their own health at risk.

This is not the entire story, though, because even when such differences are held constant statistically, persons high in conscientiousness still seem to live longer. This suggests that conscientiousness itself may reflect some underlying biological factor; what that is, however, remains to be determined. In any case, the findings of this study suggest that certain aspects of personality can contribute to living a long and healthy life.

5. Personality and Behavior in Work Settings:

Suppose you were faced with the task of choosing someone to be a salesperson; would you look for a person with certain personality traits for instance, someone who was high in friendliness and who would be comfortable around strangers? And what if your task was that of hiring someone to be a tax collector? Would you search for different traits? In all likelihood you would assume that individuals with somewhat different personalities would be most suited to these contrasting jobs.

Industrial/organizational psychologists, too, make this assumption- they believe that people will be happiest, and do their best work, when person-job fit is high; when the individuals who hold various jobs have personal characteristics (personality traits or other attributes) that suit them for the work they do. Systematic research offers clear support for this view. In particular, several aspects of the big five dimensions of personality seem to be linked to the performance of many different jobs.

For example, in one large-scale study, Salgado (1997) reviewed previous research conducted with literally tens of thousands of participants that examined the relationship between individuals’ standing on the big five dimensions and job performance. Many different occupational groups were included (professionals, police, managers, salespersons, skilled laborers), and several kinds of performance measures (e.g., ratings of individuals’ performance by managers or others, performance during training programs, personnel records) were examined.

In addition, participants came from several different countries within the European Economic Community. Results were clear- conscientiousness and emotional stability were both significantly related to job performance across all occupational groups and across all measures of performance. In other words, the higher individuals scored on these dimensions, the better their job performance.

Many other studies have confirmed and extended these results. For example, consider these findings- individuals high in conscientiousness are less likely to be absent from work than those low on this dimension, while the opposite is true for persons high in extraversion; the higher the average scores of members of work teams on conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion, and emotional stability, the higher the teams’ performance.

In sum, it seems clear that the big five dimensions of personality are related to the performance of many different jobs, and that careful attention to these aspects of personality when choosing employees might well be beneficial.

Personality and Workplace Aggression:

Atlanta, after murdering his wife and children, Mark Barton marched into two securities firms Momentum Securities and All-Tech Investment Group and calmly shot more than a dozen people; eight died. When he was finally cornered by police at a gas station, he turned his weapons on himself and committed suicide. Barton, who had previously done business with both firms, had recently experienced large losses as a result of his day-trading activities.

Incidents like this one have appeared in newspapers and the evening news with increasing frequency in recent years, and they seems to suggest that we are in the midst of an epidemic of workplace violence. Closer examination of this issue by psychologists, however, points to somewhat different conclusions.

Yes, an alarming number of persons are indeed killed at work each year more than 800 in the United States alone. In fact, however, a large majority of these victims (more than 82 percent) are murdered by outsiders during robberies or other crimes. (Barton fits this pattern; he was either firm, although he had done business with them.)

Further, threats of physical harm or actual assaults between employees are actually quite rare. In reality, the odds of being physically attacked while at work are less than 1 in 450,000 for most persons, although this number is considerably higher in some high-risk occupations such as those of taxi drivers or police.

While actual violence is indeed something of a rarity in work settings, other forms of aggression (e.g., spreading damaging rumors about someone, interfering with someone’s work in various ways) are much more common. Are some persons more likely to engage in such behavior than others? In other words, do some aspects of personality play a role in workplace aggression? The findings of recent research suggest that they do.

For instance, Type A persons report being both the victims and the perpetrators of workplace aggression significantly more frequently than Type B persons. Similarly, as you might expect, persons high in agreeableness one of the big five dimensions of personality are less likely to engage in retaliation against others for real or imagined wrongs than persons low in agreeableness.

Many factors other than personality also seems to play a strong role in determining whether, and with what intensity, workplace aggression occurs factors such as feelings of having been treated unfairly by others and unsettling changes in workplaces such as downsizing. But personal characteristics do seem important too.

This suggests that paying careful attention to these aspects of personality when hiring new employees, or offering assistance to existing employees, could help organizations reduce the incidence of workplace aggression. Clearly, this would be beneficial both to employees and to the companies where they work.